Escalating tensions between Russia and the West over the former’s annexation of Ukraine’s Crimea region may not lead to another Cold War – which was an ideological confrontation which engaged Africa in the ‘hot’ proxy wars of the superpowers. However, the Crimea incident not only radically and swiftly recalculated East-West relations, but provided a reminder that nuclear weapons are still possessed in great quantities by Russia and the West. It was just at the end of 2013 that a post-Cold War project to convert Soviet stockpiles of nuclear weapons into uranium for American nuclear power plants ended. However, large nuclear arsenals remain at a time when many analysts are expecting market prices of mined uranium to rise over the coming years as Japan, China and other leading economies reinvigorate global demand for uranium ore. The resulting increase in market demand for new uranium supplies is likely to fall to a handful of African countries, Namibia and Niger in particular, and may further produce a mini-boom in new exploration in several countries across the continent. Niger failed to reach an agreement with the French mining firm Areva on uranium extraction, which was to have been one of the year’s biggest uranium industry contracts unravelled in February 2014.(2) Mining royalties were not to the Niger government’s liking. However, the mineral is in demand now more than ever. This is good for these African nations’ economies, but has profound security implications. What of terrorists or criminals hijacking uranium supplies, sabotage of mining facilities, or even occupation of these mines by covetous neighbouring nations or international agents?

Cold War legacies

In 1993, the world faced the frightening combination of a giant Soviet-era stockpile of nuclear weapons, surging black market demand for such weapons from ‘rogue states’ and terrorists, and a deteriorating Russian security apparatus with which to protect those weapons. It was in this unique environment that the US and Russian Governments agreed to the Megatons to Megawatts programme, “a commercially financed government-industry partnership in which bomb-grade uranium from Russian nuclear warheads [would be] recycled into low enriched uranium used to produce fuel for American nuclear power plants.”(3) The 20-year programme has, to date, eliminated the equivalent of nearly 19,000 nuclear warheads, provided the feedstock for roughly 50% of the US’ nuclear power plants (or about 10% of the total American electricity market) at below-market prices, while earning Russia about US$ 8 billion in revenues for its excess nuclear stockpile.(4)

The reprocessed uranium purchased through this programme is the equivalent of about 24 million pounds of mined uranium per year,(5) or approximately 11,000 tonnes. According to the World Nuclear Association (WNA), total global production from mines in 2011 was 54,610 tonnes,(6) meaning that demand equal to as much as 20% of the current total production is about to hit the market at the end of the year. Some of this unmet future demand may be accommodated through continued demobilisation of Russian nuclear warheads, but at nowhere near current levels. Moreover, industry analysts expect demand for uranium to increase over the medium-term. Since the March 2011 Fukushima disaster in Japan, where an earthquake damaged a nuclear reactor causing local contamination and reigniting fears of nuclear disasters among citizens and policymakers around the world, uranium prices are down almost 40% and many Japanese reactors remain temporarily offline. But as one industry executive recently put it, “nuclear power is the only low-carbon-emitting generation technology that delivers large volumes of base-load power.”(7) Japanese plants will all restart operations eventually, and construction of new nuclear power plants, especially in China, will continue to drive new demand.

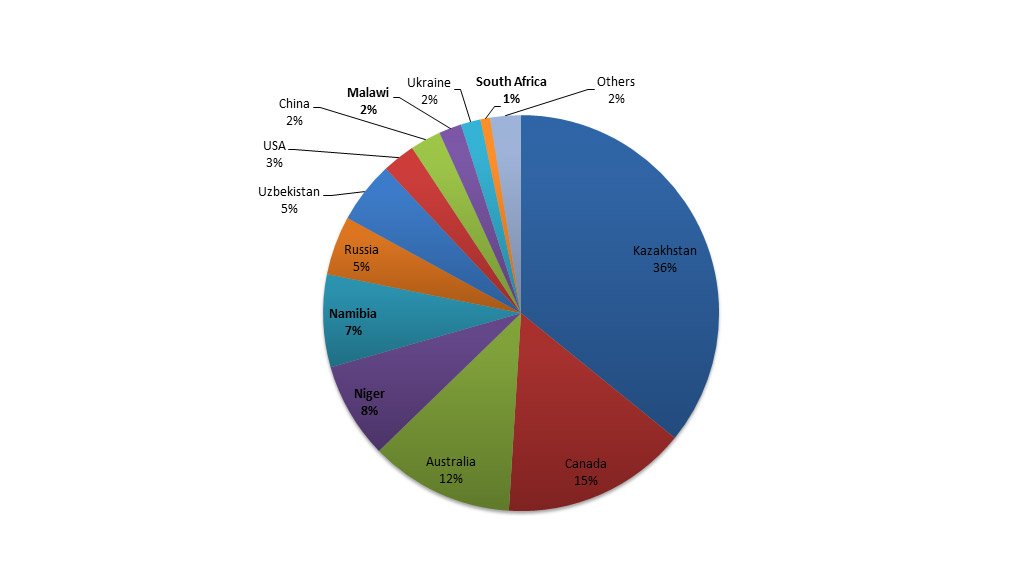

Figure 1: Where uranium originates:

Niger, Namibia, Malawi and South Africa account for 18% of global production (8)

Africa is well positioned to benefit from nuclear proliferation

This expanding demand will need to come from expanded production at existing mines or from new mines. Kazakhstan is by far the world's largest producer of uranium ore, with over 35% of the global market. But Kazakhstan's production is already at 80% of its peak capacity, and Kazatoprom, Kazakhstan's national uranium monopoly, already announced that it would cap production near present rates.(9) Canada and Australia are the world's next two largest producers, but new reserves in those countries are thought to be minimal. Indeed, production in both countries has fallen by 10% and 25% respectively since 2009.(10) Moreover, both economies’ export competitiveness have suffered from recent European financial turmoil, America's fiscal disorder and Japanese quantitative easing. Furthermore, both countries’ currencies are at or near 10-year highs vis-à-vis both the US Dollar and the Euro, making exports from both countries more expensive in international markets.

The next two global producers of uranium are Niger and Namibia, two long-time African producers, with lots of potential for expansion in production. Niger's Arlit mine is the third largest mine in the world (by current production), and of the nine new uranium mines expected to reach substantial production in the next few years, five are in Niger or Namibia.(11)

Niger’s Imouraren mine alone is set to more than double Niger's national uranium production by 2015, bringing to the market the equivalent of 10% of current global production.(12) The Husab mine in Namibia is similarly projected to double Namibia's current production, once it reaches full capacity around 2017.(13) Together, these two mines alone could fill the forthcoming demand gap left by the expiring US-Russian Megatons to Megawatts programme.ÂÂ The Valencia, Omahola and Trekkopje mines in Namibia are expected to bring to the market an annual production equivalent of either the large Imouraren mine in Niger, or the Husab mine in Namibia, adding approximately 10% of 2011 global production levels to the market.

Opportunity or resource curse?

Uranium is already a big business in both Niger and Namibia, and it is clearly poised to take on an even larger role. In Niger, the uranium industry provides up to 72% of national export revenue (depending on prices), contributes up to 5% of gross domestic product (GDP), and generates more than 5% of Nigerien tax revenue. The relative size of Namibia's uranium sector (as it currently exists) is slightly smaller by comparison, given the larger economic base of Namibia (Namibia's economy is approximately twice the size of Niger's, despite Niger's population being approximately seven times larger than Namibia). The forthcoming expansions in uranium production will expand the importance of this industry in both economies.

Given the economics of nuclear power, dependency on uranium mining is an economically different proposition than other resource dependencies such as oil, gas, copper and bauxite. As base-load power goes (something solar or wind cannot yet reliably compete at economically), nuclear plants have substantially higher fixed costs over their hydrocarbon-based rivals, including construction and fixed operating costs; but uranium as a fuel is significantly cheaper than both oil or natural gas, even given the current boom in shale gas and fracking technology. This means that once built, it makes little economic sense to pull a nuclear plant offline, even given relatively large spikes in the price of mined uranium (though political pressures, such as has recently happened in Japan following the aforementioned Fukushima disaster, can clearly bring other non-economic factors to the fore). This makes uranium mining as a base-load resource for an economy a more stable dependency in many ways, rather than oil, gas or other resources, which are more fungible with economic trends. It makes sense, then, that the two African leaders in uranium production, Namibia and Niger, are also relatively stable political economies.

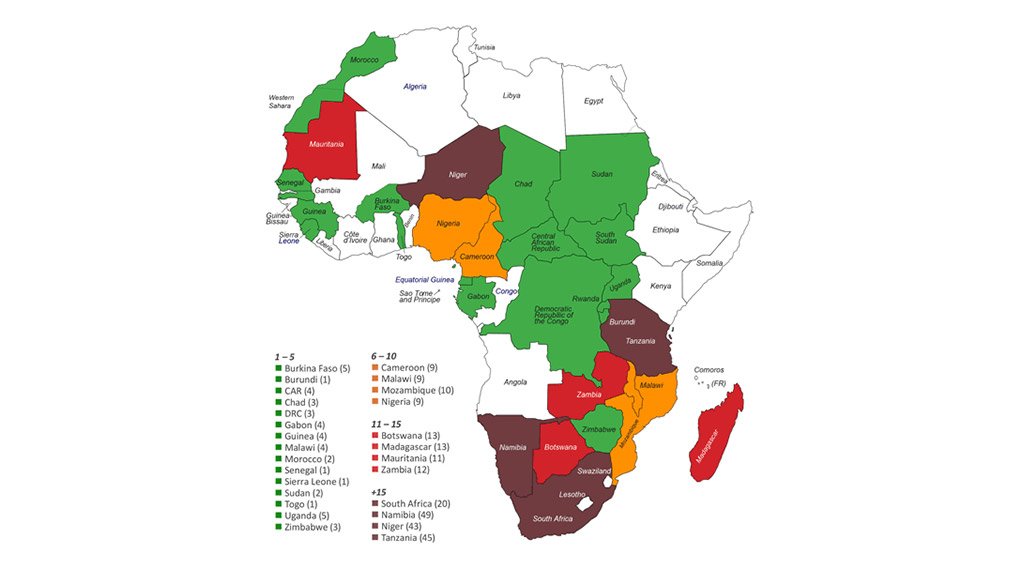

Figure 2: Africa’s wealth of mineral resources extends to significant uranium deposits located throughout the continent. The above map details countries where known uranium deposit are located and summarises the number of major companies at work excavating the valued silver-white metallic element (14)

Uranium is a lucrative, but comparatively boring, resource that may avoid some of the political traps more commonly associated with Dutch Disease resources, such as oil. Uranium mining does not typically lend itself to short-term booms that benefit loud politicians with flashy promises, but is instead an opportunity for a long-term rent that benefits responsible technocrats with long-term visions.

It is perhaps no coincidence, then, that of the 34 African countries with uranium deposits, those with current production - Malawi, Namibia, Niger and South Africa - as well as those with the most advanced development of new mines - Botswana, Morocco, Tanzania and Zambia - are all among the continent's most stable polities.

This article is extracted from the April 2014 edition of CAI’s Africa Conflict Monthly Monitor (ACMM) – the brainchild of award-winning journalist and columnist, James Hall. The +-70 page report dissects conflict trends across the African continent to guide businesses, governments, academics and other stakeholders in Africa’s growth and stability. Find out more about ACMM.

Written by Adam Choppin (1)

Notes:

(1) Adam Choppin is the Investment Analyst for ACMM and a lead analyst for emerging and frontier markets with FIS Group. Adam previously worked for several US Government agencies as a trade and economic affairs liaison in Afghanistan, Cape Verde, Ghana, Iran, Mozambique and Sierra Leone. Contact Adam at counter-proliferation@consultancyafrica.com. Edited by Dominique Gilbert.

(2) Hicks, C., ‘Niger fails to reach uranium mining deal with French nuclear firm Areva’, The Guardian (London), 28 February 2014.

(3) ‘Megatons to Megawatts’, United States Enrichment Corporation (USEC), 2013.

(4) Ibid.

(5) Bryan, C., ‘The end of the Megatons to Megawatts program (M2M)’, ProEdge Wire, 27 January 2013.

(6) ‘World uranium mining production’, World Nuclear Association.

(7) ‘Uranium industry will fight back: ERA’, Australia Mining, 6 March 2013.

(8) Chart compiled by ACMM with data from the World Nuclear Association.

(9) ‘Uranium and nuclear power in Kazakhstan’, World Nuclear Association.

(10) ‘World uranium mining production’, World Nuclear Association.

(11) Ibid.

(12) ‘Uranium in Niger’, World Nuclear Association.

(13) ‘Uranium in Namibia’, World Nuclear Association.

(14) Map by ACMM with data sourced from the German Institute of Global and Area Studies (GIGA).

EMAIL THIS ARTICLE SAVE THIS ARTICLE

To subscribe email subscriptions@creamermedia.co.za or click here

To advertise email advertising@creamermedia.co.za or click here