“Many of those affected will be members of our migrant communities – New Zealand is their home – they are us.”- New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern, reacting to the massacre, 14 March 2019

In the wake of the mosque massacres in Christchurch, New Zealand, many have admired the actions of New Zealand Prime Minister, Jacinda Ardern. It is important for us, as South Africans, to draw lessons from her actions. This is not simply to compare her leadership with our present leadership, but to see to what extent her actions can point to the qualities we need in leadership, now and in the future.

It is true that one needs more than leadership to have an emancipatory politics. One needs a people who are mobilised and organised on an informed basis in order to advance and defend democracy. But leadership remains central, a key element in driving such processes, either from state power or outside it as a force that may, at times, be best advanced outside of the corridors of official power. One way or another, leadership matters, providing or failing to provide a vision, taking decisions at difficult times and explaining to people how best to understand what they confront.

To put it simply, Prime Minister Ardern was confronted by a single white racist’s terrorist massacre of Muslims at prayer in two mosques in Christchurch. Most, or all, of those who died or attended the commemorative services were refugees from other countries.

Ardern was swift in naming the actions as terrorist murders. In a tweet on the day of the massacre, she said: “What has happened in Christchurch is an extraordinary act of unprecedented violence. It has no place in New Zealand. Many of those affected will be members of our migrant communities – New Zealand is their home – they are us.”

She and her cabinet acted immediately to tighten gun laws, banning a range of automatic and semi-automatic weapons and devices that may form components in making such weapons, just a day after the massacre. (https://www.commondreams.org/news/2019/03/21/what-real-action-stop-gun-violence-looks-new-zealand-pm-announces-ban-assault-rifles?utm_campaign=shareaholic&utm_medium=facebook&utm_source=socialnetwork&fbclid=IwAR1hjJD8o4uz-EF7Tw4Vb8WmjaUo9VeUnYYyhfzjo8xBk8EBuFNzMxARBaE).

Ardern reached out to the communities that had suffered these losses. She demonstrated compassion but she and the rest of the New Zealand leadership must also have carefully considered all the implications and consequences of these losses. Thus, when she appeared at gatherings, to express condolences, wearing a hijab, she indicated her respect but also awareness of the material losses that resulted from these deaths, including the loss of many breadwinners. She assured them that there were provisions in New Zealand law that could cover their material losses not just for weeks, she stressed, but for years. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BDxXLjDVlTU and https://www.npr.org/2019/03/15/703718075/one-of-new-zealand-s-darkest-days-shooting-at-mosques-kills-at-least-49).

Ardern left no doubt about her moral repugnance towards the killing but was also practical in taking steps to prevent further circulation of the footage that the killer had arranged to have live streamed on Facebook.

Addressing parliament for the first time after the attack, the prime minister said the accused would face “the full force of the law in New Zealand” but that she would never speak his name.

Opening with the Arabic greeting “as-salaam Alaikum”, she said the day of the attack would “now be forever a day etched in our collective memories”.

“He sought many things from his act of terror but one was notoriety, that is why you will never hear me mention his name,” she said of the gunman. “He is a terrorist. He is a criminal. He is an extremist. But he will, when I speak, be nameless.

“And to others, I implore you: speak the names of those who were lost rather than the name of the man who took them. He may have sought notoriety but we, in New Zealand, will give nothing – not even his name.”.( https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/mar/19/new-zealand-shooting-ardern-says-she-will-never-speak-suspects-name?CMP=share_btn_fb&fbclid=IwAR0llojVbPEDYntoj6m4RVX8GBAYiKJAp7nX0kVyYvzU0LX6_Eh7GhSHtDE).

Strikingly, the Prime Minister stressed that the Muslim community had come to the country, to seek safety but that she regretted the state had been unable to secure it for them. She made it very clear that New Zealand, as in the above tweet, was their home and that the losses of the Muslim community were understood by her, the government and people of New Zealand (many of whom could be seen weeping with Muslims, in television footage) as their own losses.

Female police officers who were on duty wore the hijab. It was an unprecedented level of solidarity and compassion on the part of a government and people towards a migrant community that had come under attack.

When Donald Trump, known the world over for his xenophobia, called her to offer condolences and to ask if the United States could provide any assistance she said: “Sympathy and love for all Muslim communities.” (https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/politics/111331484/pm-jacinda-ardern-told-donald-trump-send-love-to-muslims-after-mosque-shooting).

None of this was theatrical. Anyone watching the television footage can see the sorrow marking Ardern’s face but also her determination to deal with all aspects of the issue decisively and firmly.

Lessons for South Africa

This massacre comes at a time when xenophobic sentiment is being fuelled by a range of public figures, including the president, Cyril Ramaphosa, the Gauteng Premier, David Makhura and some cabinet ministers- a time when xenophobic sentiment is part of the election manifestoes of both the ANC and the DA.

What the treatment of the Christchurch massacre by the New Zealand government shows is that the way we in South Africa treat foreign nationals is not the only way this can be done, that we could choose as a country to enable those who have sought refuge here to make this their home and make them feel welcome.

It is true that foreign nationals have been made to feel welcome by many people and communities and this extends back to decades before the fall of apartheid, when communities from other parts of Africa worked in the country and settled in some townships. It is also true that many live amicably with their South African-born neighbours today. There are many cases when foreign communities have come under attack and where South Africans have helped them find shelter, retrieve their belongings and rebuild what has been damaged or destroyed.

There remains a wellspring of goodwill, a sense of common humanity that remains part of the consciousness of large numbers of South Africans. It ought to be part of the consciousness of the organised working class, given that many are schooled in the well-known slogan “an injury to one is an injury to all”. That slogan may in fact derive from biblical sources and ought also to resonate with Christian believers. Thus, Father Albert Nolan, one of the great liberation theologians of our country, has written:

“I can only presume that this is derived from the statement of Paul in I Corinthians: ‘God has arranged the body…so that each part may be equally concerned for all the others. If one part is hurt, all parts are hurt with it. If one part is given honour, all parts enjoy it’ (12:24-26). I am also reminded of Jesus saying, ‘Whatever you do to the least of my brothers and sisters, you do to me’ (Mt 25:40).” (Albert Nolan, God in South Africa. The challenge of the gospel. David Philip. Cape Town 1988, page 159).

There are also multiple examples of Koranic and local African cultural exhortations to welcome the stranger and make the stranger feel at home in one’s house. These are well known and often practised in this country. But other factors have come into play that have made foreign nationals into political footballs who can conveniently be blamed for various flaws in the social conditions of those living in poverty, without adequate health care or other social services. Instead of taking responsibility for what they have themselves brought about through stealing state resources or by condoning or colluding in such theft, leaders all too frequently point to foreign nationals as if they are parasites, eating what belongs to the citizens of South Africa.

Regrettably, the statements of the president have been part of the discourse that shifts responsibility for problems onto foreign nationals. It is part of a broader unwillingness to accept responsibility for the troubles we face, including that of ESKOM, for which leadership ought not to try to shift responsibility onto all citizens.

Strong, responsible and compassionate leadership

What we learn from the leadership of Jacinda Ardern is that even if a leader is not directly responsible for what happens under their watch, they should not try to evade responsibility for that reason. Real leaders do not run away from the problems that ensue but take firm action against the instruments that were used to cause the calamity. They also find ways of commiserating with the communities, emotionally but also materially. What is required are firm decisions but also caring, solidarity and compassion. This was once characteristic of the ANC itself.

Has the ANC-led government ever offered compensation to people or communities who have been unlawfully attacked as foreign nationals? Have they ever commiserated with these communities? Has there ever been an official presence other than that sent in to investigate alleged wrongdoing of those who have come under attack?

If that has happened, it has been done silently in an atmosphere of overall hostility that pervades government discourse and practices towards foreign nationals and indifference to their pain.

Every time the ANC condones or colludes in attacks on migrants it loses a part of its humanity and it encourages communities who usually live in peace with foreign nationals to lose theirs.

There are many people of goodwill who still do care about the pain of others, similar to the empathy now being demonstrated in New Zealand. Some of these are in the ANC and even in leadership. These people need to start rescuing this country from its shame. There is a need to restore the principle of solidarity with the wounded and identification with those who experience loss. Wherever we are, we need to join together to restore the once generous spirit of our country, and to mobilise around broader democratic tasks.

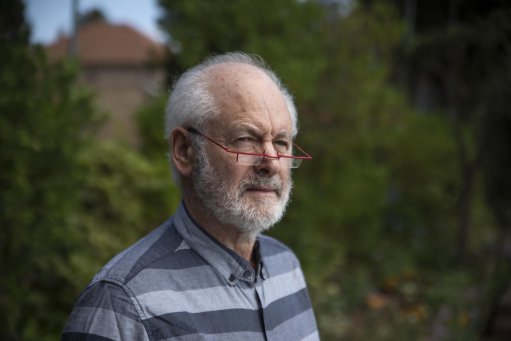

Raymond Suttner is a visiting professor in the Faculty of Humanities, University of Johannesburg, a senior research associate at the Centre for Change and emeritus professor at UNISA. He served lengthy periods in prison and house arrest for underground and public anti-apartheid activities. His writings cover contemporary politics, history, and social questions, especially issues relating to identities, gender and sexualities. He blogs at raymondsuttner.com and his twitter handle is @raymondsuttner