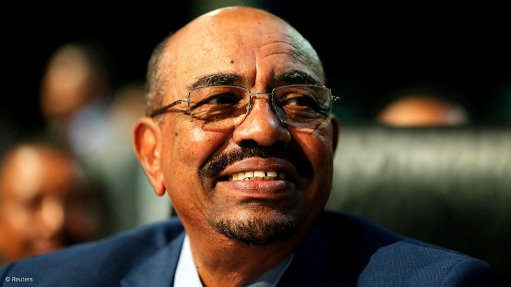

President Omar al-Bashir

Photo by: Reuters

South Africa is losing its moral standing on the global front, and could soon be regarded as a rogue nation, an Institute for Security Studies seminar on the implications of the Omar al-Bashir saga heard on Thursday.

Howard Varney, a senior consultant at the International Centre for Transitional Justice, and deputy justice minister John Jeffery debated the implications of the Sudanese President’s controversial departure from South Africa during the 25th African Union summit that took place in Cape Town in June. South African authorities failed to detain al-Bashir despite an International Criminal Court warrant of arrest against him.

“Sadly, I don’t believe South Africa enjoys the standing and respect it used to have when it comes to the question of our law in international affairs in particular the international criminal justice,” Varney said.

“In fact…I think we might become seen as a problem state and if we carry on in this route of being party to treaties which we simply treat with contempt we are well on the way to becoming a rogue state.”

He said the affidavit filed by the state, explaining the reasons why Al-Bashir managed to leave Pretoria despite an interim high court order barring his exit from the country, showed that government prioritized politics over the law.

Jeffery said had Bashir been arrested by South African authorities, there would have been “severe consequences”.

“When George Bush was president and he came here, if somebody wanted to arrest him under the Convention Against Torture, I don’t think the Americans would have sat by and allowed their president to be arrested,” Jeffrey said.

“That is a practical element.”

Varney disagreed, stating South Africa had now been plunged into “a grave constitutional crisis”.

“In my view there was an open and brazen defiance of the court order,” he said.

“Secondly, there was brazen refusal to comply with our treaty obligations under the Rome Statute. These are remarkable things to do for a state which professes to be part of the community of nations.”

Varney said the Bush argument advanced by Jeffery did not hold water.

“It’s no use putting up the example of George Bush. I believe that George Bush has a lot to answer for, but there is no indictment against him,” he argued.

“If he [Bush] were to come, there is no basis to arrest him, certainly under the Rome Statute. No indictment has been issued under any other law for that matter.”

Varney said even though African countries have gripes with the International Criminal Court (ICC), as long as they remain members, they have a strong obligation to abide by the ICC treaty.

“I don’t believe it is good enough to say that because we believe the treaty is being applied in a biased fashion, or that the court order was incorrectly made, therefore we abandon it,” he said.

Jeffery countered that the Bashir incident should not be “over-dramatised”.

“The chief justice is on record saying generally government abides with court orders. Yes, there is a problem in some instances because government is very big. There are issues of not knowing about the court orders because of problems with the bureaucracy,” said Jeffery.

“It is something we are concerned about. We want to ensure that court orders are met. At the same time, there is recognition that the state is a slightly different animal…If we didn’t care about court orders, we wouldn’t be appealing the court judgement.”

The ISS managing director, Anton du Plessis, who was moderating the debate, said South Africa had never produced so many international criminal justice “experts” than after the Bashir visit.

Bashir’s visit sparked heated debate in South Africa after the controversial leader joined other African heads of state at a flamboyant summit hosted at the Sandton International Convention Center last month.

The ICC has an outstanding warrant of arrest for Bashir. He is accused of genocide and other crimes against the people of Sudan’s western Darfur province. As a signatory to the ICC, South Africa was obliged to arrest him.

However, Bashir was allowed to leave the country in spite of an interim order by Pretoria High Court Judge Hans Fabricius, who had ordered that Bashir remain in the country pending a final ruling on the ICC arrest warrant.

This led to a scathing rebuke of government by North Gauteng High Court Judge President Dunstan Mlambo and a full bench of the court. They demanded an explanation as to why the Sudanese president had been allowed to leave, going so far as recommending that the National Director of Public Prosecutions should consider initiating criminal charges over the incident.

On Tuesday, government formally lodged an application for leave to appeal the high court judgement which found that the state failed in its mandate by not arresting Bashir.