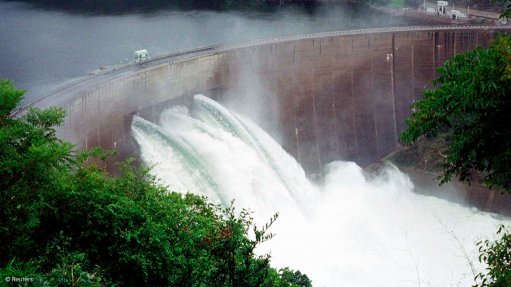

Kariba Dam

Photo by: Reuters

Should the Kariba dam, a hydroelectric dam in the Kariba Gorge of the Zambezi river basin between Zambia and Zimbabwe, collapse, it would be the beginning of years of economic, social, environmental, humanitarian and technological fallout that would devastate Southern Africa’s economies.

Further, new projects and investment in the region would be severely compromised, as the ongoing lack of electricity and water would make these uneconomical, potentially for up to eight years, while the dam was rebuilt.

These predictions were made by Kay Darbourn, a member of the Institute of Risk Management South Africa (Irmsa), in a report, ‘Impact of the Failure of the Kariba Dam Risk’, which highlighted the risks and challenges for the Southern African region related to the current state of the dam, as well as its proposed rehabilitation project.

The report said engineers had warned that without urgent repairs, the entire dam would collapse and a tsunami would flow over the Zambezi Valley and reach the Mozambique border within eight hours.

The torrent was expected to overwhelm Mozambique’s Cahora Bassa dam and destroy 40% of Southern Africa’s hydroelectric capacity. Consequently, Darbourn foresaw electricity-strapped South Africa losing out on 1 500 MW of contracted power from Cahora Bassa, from which electricity was transmitted to South Africa using a 1 420 km high-voltage direct current line, for at least five years.

The Zambezi River Authority had estimated that the disaster would put the lives of 3.5-million people at risk.

The report, written and researched by Darbourn, was launched on Thursday by Irmsa and risk management and report sponsor, insurance broking firm Aon South Africa.

Darbourn began her research following a report by the British Broadcasting Corporation, in 2014, that highlighted the dangerous state of Kariba.

According to the report, torrents from the dam’s spillway had eroded the seemingly solid bed of basalt the dam was built on in 1959.

As a result, a large crater was formed and undercut the dam’s foundations.

Darbourn noted that the dam’s six floodgates needed repair and added that the rehabilitation project for the dam had already secured most of the required funding from the African Development Bank, the World Bank and the European Union.

The project was expected to be complete in 2025; however, project delay from any cause, as well as climate change, high rainfall patterns that would impact future dam levels and potential seismic activity could contribute to the likely failure of the Kariba dam, she said.

“Whether you are a shareholder, stakeholder, board member, business executive, risk manager or even private individual, if you live, work, own property or have investments in South Africa, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Botswana, Mozambique or Malawi, the chances are that if the Kariba dam fails, you will be affected,” warned Darbourn.