African National Congress (ANC) politics over the last few weekends has been dominated by leadership elections. This weekend a man just one month below the threshold for membership of the ANC Youth League (ANCYL) of 35 years of age, Collen Maine, was elected to its presidency. He is said to have done so with the assistance of what is called the “Premier League” (the Premiers of Free State, Mpumalanga and North-West).

This grouping is said to have also played a significant role in securing the victory of Bathabile Dlamini, elected as president in the ANC Women’s League (ANCWL) conference. The defeated president of the ANCWL, Angie Motshekga, had criticised interference as a manifestation of “patriarchy”, though the central platform of Dlamini’s election was the need for a woman to be president of the ANC.

The members of the Premier League are premiers known to be close to President Jacob Zuma – unlike, for example, the Gauteng leadership – and it must be assumed that they would not have intervened without his blessing.

The election of Dlamini, with her pledge to see a woman as president, was followed by a report in the Sunday Times that Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma confirms she is available for election to succeed Zuma as president of the ANC, and ultimately of the country. Of course, this is framed within the discourse of current ANC-speak. One has the “responsibility” to accept any position for which one is nominated in the ANC, which is just “how it works” within the time-honoured traditions of the organisation. Any person who is a disciplined cadre, so it goes, just accepts deployment to any position, high or low, whether one likes it or not. One’s own needs are submerged within the needs of the collective to which one has pledged one’s loyalty. That is said to be what it means to be a disciplined cadre. Thus Dlamini-Zuma is reported in the Sunday Times to have said, “In the ruling party, you never refuse a responsibility. I have never refused any responsibility that the ANC asked me to do.”

Likewise, Dlamini-Zuma cannot confirm that she will stand for president, for that is not how it is done in the ANC. One just gets called to serve and the call, which is usually said to emanate from the branches, is one that a disciplined cadre has to answer within the demands of the discipline that goes with membership and especially one in a leadership position. This is how she answered the Sunday Times question whether she was in the running for the presidency: “But I can’t answer such a question. Any person in the ruling party knows that I cannot answer the question.”

The Sunday Times claims that her potential presidential bid is said to enjoy the support of the “Premier League”, but that it stands against the “ANC tradition” for an incumbent president to be succeeded by his deputy.

What is striking about these reports is that there is apparently no question of political vision involved, no stated difference in strategies over how the problems of the country are addressed, what approaches will be deployed in order to remedy the various ills that beset the South African polity.

In the main we confront competing clientelist networks, promoting one rather than another set of patron/client relationships, ensuring that one group of people rather than another will be serviced depending on who is elected. This happens at every level of the organisation and through that organisational link, in holding ANC office, individuals are elected or appointed to hold positions in government. Holding office is not perceived primarily as representing or pursuing one or other policy, but the capacity to ensure that certain individuals benefit in one or other way. The stakes are high insofar as the benefits derived from allocating positions can make a considerable difference to the material status of individuals.

But the patronage works not only to secure benefits but also to defend patrons and clients from coming to harm. That may seldom arise in that in most cases it may be that intra-organisational competition for positions does not flare up into violence. Equally it usually does not involve the state in the sense of an incumbent facing potential harm from the state, but some interventions may be necessary to ensure that some individuals are not prosecuted or that they should be released from prison on one or other pretext as with Shabir Shaik or that they should have their criminal record expunged. The latter happened when Zuma expunged the criminal record of Mr Booker Nhantsi, husband of Nomgcobo Jiba, controversial deputy head of the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA), who had been convicted, as an attorney, of stealing a client’s trust money.

But tensions have flared within the organisation and the eThekwini ANC region has failed to hold its elective conference for some months. In some provinces, like Mpumalanga, KwaZulu-Natal and North-West there have been intra-ANC and intra-alliance physical conflicts and in some cases deaths have resulted.

But at the highest-level stakes have become higher for another reason, related to state power, with the potential reinstitution of charges against President Jacob Zuma. It may well be that the involvement of the “Premier League” bears some connection with this. For if Zuma is prosecuted it may well be that wrongdoing can be uncovered in other quarters, including that of the leaders of the Premier League, and they too can be prosecuted.

And this may be one of the reasons why there is a sudden eagerness to ensure that “a woman” becomes president (meaning that Cyril Ramaphosa should not become president). We can discount the possibility of a resurgence of feminism, since questions of women’s empowerment count for little in the calculations of the ANCWL and the Premier’s League.

As the possibility of reinstitution of charges against Zuma looms larger and is already on the agenda of the courts, it has become known that this matter will in all likelihood only be settled over some years and possibly after Zuma has completed his term of office as state president.

What then becomes important, if the courts decide that the charges should be reinstituted or that the matter should be referred back to the NPA for review, is: who will make the decision whether or not to prosecute? More importantly, who will then decide whether the incumbent NPA head or some other person is the right person to make such a decision?

The question then arises whether Cyril Ramaphosa can be “trusted” to do the “right thing”. Ramaphosa may have gone to great lengths to demonstrate his loyalty to Zuma. He may have demeaned himself with repeated professions of loyalty and the declaration on his return to leadership that he was to join the “crème de la crème”. He may have used many occasions to offer effusive praise for the qualities of leadership, which he has identified in Jacob Zuma. But that may not satisfy the suspicion that he may see himself as a leader who is entitled to assert an element of independence. That may be feared to be potentially detrimental to Zuma (and in the long run others who could be prosecuted if the law were to be free to take its course).

It is not thereby to assert that Ramaphosa has shown any greater commitment to constitutionalism and legality than others in government who have been party to attacks on foreign migrants, defiance of the courts over Omar al-Bashir and other underminings of constitutionalism and general failures to provide basic needs like shelter, clean water and adequate educational facilities. It is true that Ramaphosa was a key figure in making the current constitution, but clearly in the almost 20 years since then, sentimental attachment to the document has been displaced by hard-nosed decisions that have been beneficial to Ramaphosa himself.

Clearly this is a clientelist factor that goes beyond ensuring that rewards and loyalties that exist continue after the departure of Zuma from office. Zuma may not expect to rule beyond his tenure, but he does need protection from the power of the law and it may be that his ties with his former wife Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma are sufficiently strong to ensure that he will not be prosecuted or at any rate they are of a different quality than whatever ties may bind him to Ramaphosa.

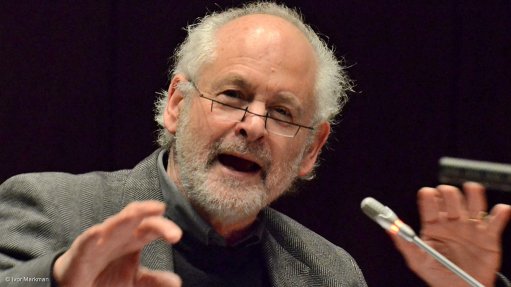

Raymond Suttner is a professor attached to Rhodes University and UNISA. He is a former ANC underground operative and served over 11 years as a political prisoner and under house arrest. He writes contributions and is interviewed regularly on Creamer Media’s website polity.org.za. He has authored or co-authored The Freedom Charter-the People’s Charter in the Nineteen-Eighties (UCT, 1984) 30 Years of the Freedom Charter (Ravan Press, 1986), Inside Apartheid’s Prison (UKZN Press, 2001), 50 Years of the Freedom Charter (UNISA Press, 2006), The ANC Underground (Jacana Media, 2008) and Recovering Democracy in South Africa (Jacana Media, 2015). His twitter handle is: @raymondsuttner and he blogs at raymondsuttner.com.