The president of Equatorial Guinea, Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo, once described the discovery of oil in the 1990s off the coast of the small Central African nation as “manna from heaven,” the Biblical life-saving bread that God sent Israelites as they wandered in the desert.

Ravaged by almost six centuries of colonialism followed by an eleven-year brutal dictatorship, the country was one of the world’s poorest and most poorly governed in 1979 when Obiang deposed his uncle and took power.

The discovery of oil in 1991 had the potential to change the fortunes of Equatorial Guinea, and it did, in many ways. Before the discovery of oil the country’s total income was US$132 million, or $330 per capita. Within the next decade per capita gross domestic product (GDP) rose significantly, comparable to that of many industrialised nations—peaking in 2012 at $19 billion ($24,304 per capita).

However, oil production has been in decline since 2012, and oil is expected to run dry by 2035 unless new reserves are found.

Suddenly the small country of about one million people occupying 28,050 square kilometers had a great but fleeting opportunity to deliver exemplary social services to its citizens in line with its human rights obligations. Obiang raised expectations, repeatedly saying he would prioritise health services and education, but budgetary allocations to health and education have in fact been dismal: in 2011, the most recent year for which there is data, the government spent three percent of its budget on education and less than two percent on health, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

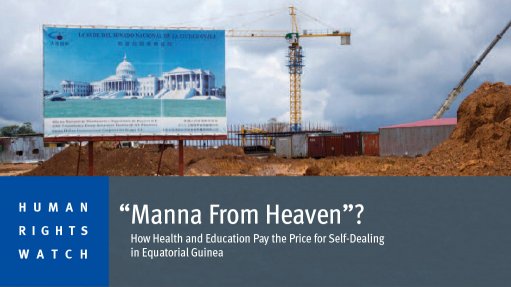

Forty-five other countries in Equatorial Guinea’s per capita GDP range spent at least four times as much on health and education during the same period. Instead the country invested heavily in large-scale infrastructure projects, which comprised 82 percent of its total budget in 2011, an approach the IMF and World Bank have repeatedly criticised.

Report by the Human Rights Watch