As is evident in discord voiced in the media, the ANC is still reeling after the setbacks it experienced in the local government elections of 3 August.

It may be that specialists in analysing election statistics argue that the ANC has been less weakened in the rural areas than in urban areas, and that the extent of the DA victory may be less than it appears. Nevertheless, at a symbolic level it remains a substantial defeat.

Whether or not this is a precursor to national loss of political power remains to be seen, and there remain many hurdles to be overcome before the DA or any combination of forces can hope to achieve a national majority, with or without some type of alliance.

It remains very important that the DA now has control, sometimes with the support of coalition partners, sometimes with EFF support (but outside of a coalition), ensuring its majority of three key metros, with a total budget of R287-billion.

For all the exaggeration there may be about DA efficiency it is likely that they will run the metros now under their control more efficiently than the ANC has. They have a powerful incentive to “deliver” and as a new council have no reason to be complacent. They have “something to prove”. If they do perform significantly better than the ANC has done, the “nightmare” that the ANC faces is that it may not be possible to regain control of these metros in the foreseeable future

It is said that those black people who misguidedly voted for the DA will soon learn that their fate is far worse under DA rule. The DA is already accused of racism in the Western Cape, and there is no doubt that Cape Town is a very unequal society with continuing dehumanised and dangerous conditions in black and especially African areas.

But the ANC cannot claim to have unequivocally championed the wellbeing of the impoverished and oppressed majority. The ANC has often failed to meet their basic needs, where the resources were available.

But more insidiously, structural racism has been perpetuated in many respects. This is manifested, among other ways, by the mode of operation of public and private policing, where black people are presumed to be potential criminals and stopped or harassed, or find themselves facing charges or arrest, while whites drive or walk past without hindrance. We know, of course, that structural racism and inequality are also found in educational institutions and a number of other sites of public and private existence.

In other words, if the DA does practise racially discriminatory practices and entrench inequalities, it will not be inventing something new but perpetuating the legacy of the ANC in the areas it has governed.

At a more general level the ANC appears ideologically bankrupt, making little contribution to public life and thinking. There was a time when the ANC and SACP evoked debates through its statements and position papers. That is no more. ANC statements are unconvincing, clichéd and do not inspire much interest.

Despite still being the largest political organisation and being the national government of the day with control of key state institutions, the ANC nevertheless creates an impression of incoherence. There is publicly displayed disunity in the ANC itself and within the ANC-led alliance, especially in relation to the SACP in recent times. There are also, possibly to an unprecedented extent, openly contradictory statements by various office bearers.

Whatever hegemony, in the sense of moral and intellectual consent, that the ANC once enjoyed has disintegrated. It is viewed with considerable cynicism. In spite of this defeat – for it was a defeat – every linguistic stratagem the ANC uses has little conviction and zero persuasive power in its attempts to depict the defeat as a victory or less decisive setback than it was.

Much of the blame for the ANC’s setbacks as well as its declining moral support can be attributed to the president, Jacob Zuma, and the character of his leadership. He manifests seemingly contradictory qualities. At once he appears absent, yet what he wants to happen is executed or attempted to execute by others, whether or not he is visible as a decision-maker.

He has suffered setbacks but this does not seem to have made him more cautious, and may possibly have made his attacks on individuals and democratic institutions more aggressive and thoroughgoing. Despite the local government elections constituting some sort of judgement on the pillage of state resources there seems, now, to be a more gross, single-minded attempt to take over state apparatuses and divert these towards private benefit.

It is in this context that we need to understand the attack on the Treasury and the Finance Minister, Pravin Gordhan in particular, through abuse of the power of the Hawks. There is simultaneously a push-back, a resistance from the side of the Treasury, but also investors reacting negatively, withdrawing or threatening to withdraw their stake in South Africa, as a result of these attacks on custodians of public finance.

The local government elections were both a watershed moment and confirmation of what some were reluctant to recognise. It was a watershed moment insofar as nationalist mythology was confronted by documentary evidence of the liberation movement’s rejection by the people whose “sole and authentic representatives” they were meant to be (in the words of international organisations at the time of the struggle) in perpetuity or in Zuma’s words “until Jesus’s return”. The elections provided evidence to the contrary, not something that could be dismissed as simply the work of malcontents or racists, but in some key areas, rejection by the ANC’s core constituency.

One ought to pause and consider what it means to have been defeated in Nelson Mandela Bay, the area where there must be more Robben Island prisoners per square kilometre than any other part of the world. It was a place that lived, breathed and loved the ANC, the home of Govan Mbeki and Ray Mhlaba, amongst others. Johannesburg produced many of the organisation’s giants, who became legends in the struggle – AB Xuma, Anton Lembede, Walter and Albertina Sisulu, Nelson Mandela, Oliver Tambo, Lillian Ngoyi, Bram Fischer, Ruth First and many others. In the Tshwane area, one also found early ANC leaders including SM Makgatho, who succeeded John Dube as president, Simon Peter Matseke, Stephen Tau and later Peter Nchabeleng and Frances Baard, who were in Pretoria for much of their political life.

The ANC held the reins of power in a period when a number of inherited problems had to be addressed partly before having the resources to do this. It could not deliver fully on the promise of a better life, initially, even where some urgent needs had to be addressed. But the problem that arose was that even when this capacity increased and the resources were there, it still failed to meet basic needs in many cases. In a significant number of situations the ANC government has been proved to have diverted resources intended for the poor into private pockets.

The ANC lost more than electoral support and it lost this before the elections. It ruptured a connection with the people who were its traditional base and it lost that link because it betrayed them.

The ANC betrayed the trust that had been built over decades of struggle from the organisation’s early beginnings through decades when it was overshadowed by other organisations which had a broad mass base long before the ANC (like the Garveyites and the Industrial and Commercial Workers Union, the ICU).

As it gradually gained support, notably in the 1950s, it engaged in different forms of resistance, surviving vicious repression. Having forged that connection with its base, it has now betrayed it. It was a link that existed between an organisation that was loved by a people who saw it as the only force that would restore their dignity and sense of self-worth, that would right the wrongs wreaked on them over centuries.

The ANC did not need elections to recognise that it had severed its relationship with those who loved the organisation, who grew up in the organisation or in families that belonged to the organisation over generations, in a time when many of its leaders were exemplary in their conduct.

The ANC of today has forfeited this moral capital, which it enjoyed until relatively recently. In recent times it has acted in a manner that has been callous, cruel, greedy, and hurtful to its own core constituency. In its indifference to suffering, even through acts that have caused death, it has been seen to violate the bond with those who trusted it with everything.

It may be asked why this rupture did not happen earlier. For very many the ANC represented a way out of misery, an organisation that at one stage did its best for its constituency. When it became the government, when people did not always get that which they needed or that to which they were entitled, they remained relatively patient, because they considered this to be their organisation. It had proved itself over decades, suffering with or on behalf of the oppressed people.

What is the future trajectory of the ANC? It is difficult to see the organisation recovering the ground that it has lost in the short run, especially when it is engaged in intense internal battles. For it to recover the moral high ground, as urged by the Gauteng ANC, is even more difficult to visualise since it will mean uprooting practices that have been established over the last two decades. The suggestion that the ANC always “self-corrects” or can return to its “true self”, is rather difficult to imagine, and what that “true self” is may well be subject to considerable debate.

For those who observe what is happening from the outside, the conflicts within the ANC cannot be allowed to determine the future of our democracy. It has been said that there is and can be politics outside of the ANC and beyond electoral contestation. No site on its own can be the exclusive place where democracy is realised. It is important that we build our democratic voices in a range of places that cumulatively contribute towards the regeneration of our freedom.

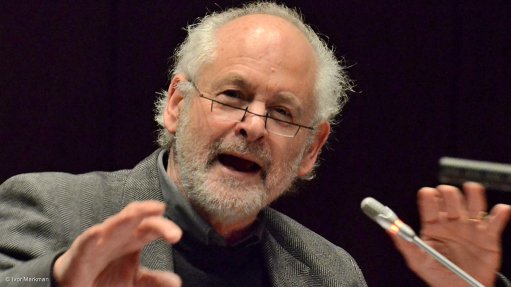

Raymond Suttner is a scholar and political analyst. He is a former political prisoner for activities in the ANC-led liberation struggle. Currently he is a Part-time Professor attached to Rhodes University and an Emeritus Professor at UNISA. His most recent book is Recovering Democracy in South Africa (Jacana and Lynne Rienner, 2015). He blogs at raymondsuttner.com and his twitter handle is @raymondsuttner